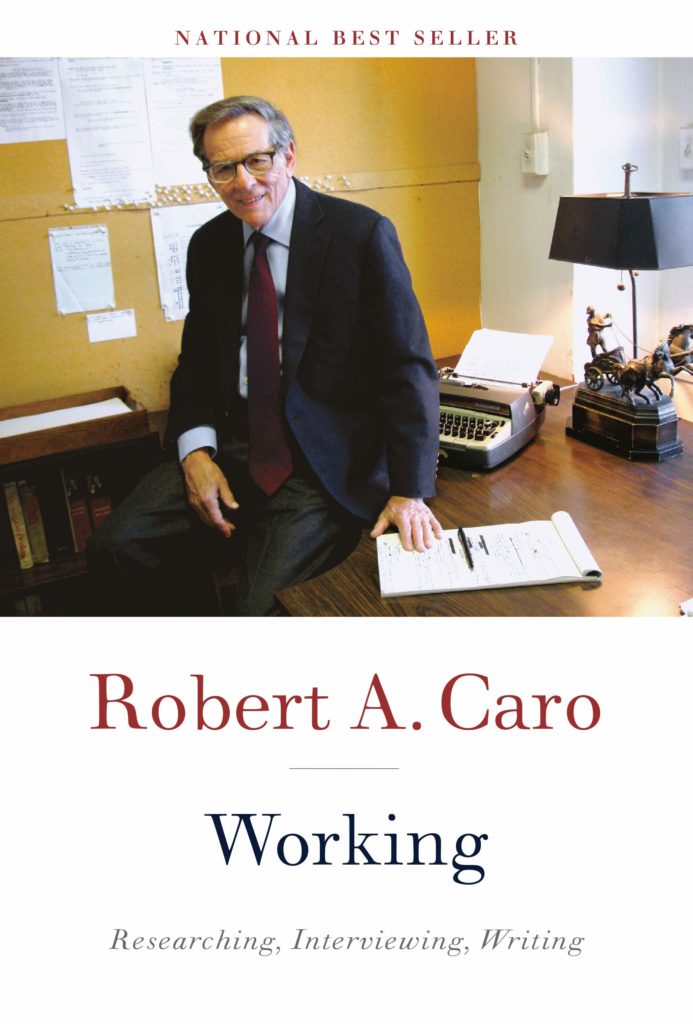

This week I read Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing, written by Robert A. Caro. Caro is known for his books, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, and the four volumes of The years of Lyndon Johnson.

Caro wrote the intention of this book is to share some of his experiences and thoughts while writing his books. This book is about what Caro learned or discovered about the writing of biography or more broadly nonfiction; and more, what he discovered about himself over the years of his professional career. For example, while riding the polls, “a row of tiny dots on a map helped lead me to the realization that in order to write about political power the way I wanted to write about it, I would have to write not only about the powerful but about the powerless as well—would have to write about them (and learn about their lives) thoroughly enough so that I could make the reader feel for them, empathize with them, and with what political power did for them, or to them.”

I chose to read this book, not because of Robert Caro’s fame, admittedly that helped to establish the credibility of this book, but because I want to know what it was like for writers like Caro to write great non-fiction.

I had this image that the process and useful skills for writing the type of books Caro wrote is similar to doing a good PhD program: know your subject more thoroughly than anyone else, perform magic distillation with some elements of innovation, and cherry-pick what to include in the final thesis and so on; it seems that the hardest part might be to know what threads to follow, to have the skills to go deeply underneath the surface, to be able to see the forest beyond the trees, finally and probably most importantly, to tell the stories well.

This book satisfied my craving temporarily. As another great piece of nonfictional writing from Caro, its candidness and simplicity touched me most. I look forward to reading Caro’s memoir, a full-scale one as he calls it, when it is available.

“But you’re never going to achieve what you want to, Mr. Caro, if you don’t stop thinking with your fingers.”

When I decided to write a book, and, beginning to realize the complexity of the subject, realized that a lot of thinking would be required—thinking things all the way through, in fact, or as much through as I was capable of—I determined to do something to slow myself down, to not write until I had thought things through. That was why I resolved to write my first drafts in longhand, slowest of the various means of committing thoughts to paper, before I started doing later drafts on the typewriter; that is why I still do my first few drafts in longhand today; that is why, even now that typewriters have been replaced by computers, I still stick to my Smith-Corona Electra 210. And yet, even thus slowed down, I will, when I’m writing, set myself the goal of a minimum of a thousand words a day, and, as the chart I keep on my closet door attests, most days meet it. It’s the research that takes the time—the research and whatever it is in myself that makes the research take so long, so very much longer than I had planned.

It gradually sank in on me that I was hearing a story of a magnificent kind of courage, the courage of the women of the Hill Country, and, by extension, of the women of the whole American frontier.

I’m not going to suggest that spending those three years learning about the Hill Country was a sacrifice. Getting a chance to learn, being forced to learn—really learn, so that I could write about it in depth, so that I could at least try to make it true to reality, to make the reader feel the harshness of the fabric of these women’s lives—being given an opportunity to explore, to discover, a whole new world when you were already in your forties, as Ina and I were: that wasn’t a sacrifice; being able to do that was a privilege, exciting. The two of us remember those years as a thrilling, wonderful adventure.

If in even small measure I told it for them, these women of the American frontier, and in order to accomplish that, The Path to Power took a couple of years longer to write, well—so what?

People are always asking me why I chose Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson to write about. Well, I must say I never thought of my books as the stories of Moses or Johnson. I never had the slightest interest in writing the life of a great man. From the very start I thought of writing biographies as a means of illuminating the times of the men I was writing about and the great forces that molded those times—particularly the force that is political power.

“Turn every page. Never assume anything. Turn every goddamned page.”

Underlying every one of my stories was the traditional belief that you’re in a democracy and the power in a democracy comes from being elected. Yet here was a man, Robert Moses, who had never been elected to anything, and he had enough power to turn around a whole state government in one day. And he’s had this power for more than forty years, and you, Bob Caro, who are supposed to be writing about political power and explaining it, you have no idea where he got this power. And, thinking about it later, I realized: and neither does anybody else.

I began to feel that I was starting to glimpse, through the mists of public myth and my own ignorance, the dim outlines of something that I didn’t understand and couldn’t see clearly but that might be, in terms of political power, quite substantial indeed.

And he remembered things a lot bigger than votes, or decisions, and in the remembering taught me about something much larger than the workings of politics: about a particular type of vision, of imagination, that was unique and so intense that it amounted to a very rare form of genius—not the genius of the poet or the artist, which was the way I had always thought about genius, but a type of genius that was, in its own way, just as creative: a leap of imagination that could look at a barren, empty landscape and conceive on it, in a flash of inspiration, a colossal public work, a permanent, enduring creation.

I also understood better the mind of a sculptor who wanted to sculpt not clay or stone but a whole metropolis: I saw the genius of the city-shaper. When he talked, moreover, you saw how the dreams—and the will to accomplish them—were still burning, undimmed by age.

Then I asked him if he had ever been worried about losing to the people up there—of having to change his route to save their homes. “Nah,” he said, and I can still hear the scorn in his voice as he said it—scorn for those who had fought him, and scorn for me, who had thought it necessary to ask about them. “Nah, nobody could have stopped it.” In fact, he said, the opposition hadn’t really been much trouble at all. “[They] just stirred up the animals there. But I just stood pat, that’s all.” He looked at me very hard to make sure I understood, and, intending to return to the subject in more depth at some future date, I said that I did.

To those farmers, the day they heard that “the road was coming” would always be remembered as a day of tragedy. One consideration alone made the tragedy more bearable to them—their belief that it was necessary, that the route of the parkway had been determined by those ineluctable engineering considerations.

But these conversations with the Long Island farmers had brought home to me in a new way the fact that a change on a map—Robert Moses’ pencil going one way instead of another, not because of engineering considerations but because of calculations in which the key factor was power—had had profound consequences on the lives of men and women like those farmers whose homes were just tiny dots on Moses’ big maps. I had set out to write about political power by writing about one man, keeping the focus, within the context of his times, on him. I now came to believe that the focus should be widened, to show not just the life of the wielder of power but the lives on whom, and for whom, it was wielded; not to show those lives in the same detail, of course, but in sufficient detail to enable the reader to empathize with the consequences of power—the consequences of government, really—on the lives of its citizens, for good and for ill. To really show political power, you had to show the effect of power on the powerless, and show it fully enough so the reader could feel it.

It wasn’t something about which, I had learned the hard way, I had a choice; in reality I had no choice at all. In my defense: while I am aware that there is no Truth, no objective truth, no single truth, no truth simple or unsimple, either; no verity, eternal or otherwise; no Truth about anything, there are Facts, objective facts, discernible and verifiable. And the more facts you accumulate, the closer you come to whatever truth there is. And finding facts—through reading documents or through interviewing and re-interviewing—can’t be rushed; it takes time. Truth takes time.

Its base, the base of all history, of course is the facts, it’s always the facts, and you have to do your best to get them, and get them right. But once you have gotten as many of them as possible, it’s also of real importance to enable the reader to see in his mind the places in which the book’s facts are located. If a reader can visualize them for himself, then he may be able to understand things without the writer having to explain them; seeing something for yourself always makes you understand it better.

His father had been the man of optimism—“great optimism.” Lyndon had seen firsthand, when his father failed, the cost of optimism, of wishful thinking. Of hearing what one wants to hear. Of failing to look squarely at unpleasant facts. Because his father purchased the Johnson Ranch for a price higher than was justified by the hard financial facts, Lyndon Johnson had felt firsthand the consequences of romance and sentiment. Optimism—false optimism: for many people, it’s just an unfortunate personal characteristic. For Lyndon Johnson, it was the bite of the reins into his back as he shoved, hour after hour, under that merciless Hill Country sun, pushing the Fresno through the sun-baked soil.

What mattered to him was winning, because he knew what losing could be, what its consequences could be.

Interviewing: if you talk to people long enough, if you talk to them enough times, you find out things from them that maybe they didn’t even realize they knew.

my books are an examination of what power does to people. Power doesn’t always corrupt, and you can see it in the case of, for example, Al Smith or Sam Rayburn. There, power cleanses. But what power always does is reveal, because when you’re climbing, you have to conceal from people what it is you’re really willing to do, what it is you want to do. But once you get enough power, once you’re there, where you wanted to be all along, then you can see what the protagonist wanted to do all along, because now he’s doing it. With Robert Moses, you see power becoming an end in itself, transforming him into an utterly ruthless person. In The Passage of Power, I describe the speechwriter Dick Goodwin trying to find out if Johnson is sincere about civil rights, and Johnson tells him, I swore to myself when I was teaching those kids in Cotulla that if I ever had the power, I was going to help them. Now I have the power and I mean to use it. You see what Johnson wanted to do all along. Or at least a thing he wanted to do all along…

You have to write not only about the man who wields the sword, but also about the people on whom it is wielded.