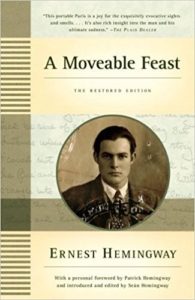

A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway was first published posthumously in 1964. It covers Hemingway’s time spent in Paris from 1921 to 1926 as a struggling journalist and his gradual transition from a journalist to a writer.

I first read this book on my way from Silicon Valley to Sandia National Laboratories some years ago. That business trip turned out to be one of the most memorable events during my years working on Exascale Computing. To a certain extent, that experience still has a penetrating impact on my career decision making. The story or maybe stories sprung from there have been to be told in a separate blog though. Thanks to this book, I travelled to Paris to trace the walks and places that Hemingway wrote in this book this past February. They were very cold and wet days with miles of walks every day, but my time spent there brought Hemingway and his writing much closer to me.

The most important takeaway for me from this book is: it is perfectly normal to struggle miserably to write. It seems to me that the mental and physical struggles help one write more sharply and closer to the truth. This might not be Hemmingway’s intended key message for the book. Chinese philosopher Mengzi wrote: “天降大任于斯人也,必先苦其心志,劳其筋骨,饿其体肤,空乏其身,行指乱其所为,所以动心忍性,曾益其所不能.” Sadly in translation, much of it is lost. We need to learn to read in its original language to appreciate it fully. Nevertheless, one translation I found is: “when Heaven is about to confer a great office on any man, it first exercises his mind with suffering, and his sinews and bones with toil. It exposes his body to hunger, and subjects him to extreme poverty. It confounds his undertakings. By all these methods it stimulates his mind, hardens his nature, and supplies his incompetencies.” One would say that Hemingway’s time in Paris fit into Mengzi’s prescription well.

Some of my favorite passages from the book:

It was wonderful to walk down the long flights of stairs knowing that I’d had good luck working. I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day. But sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that you knew or had seen or had heard someone say. If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written. Up in that room I decided that I would write one story about each thing that I knew about. I was trying to do this all the time I was writing, and it was good and severe discipline.

“You can either buy clothes or buy pictures,” she said. “It’s that simple. No one who is not very rich can do both. Pay no attention to your clothes and no attention at all to the mode, and buy your clothes for comfort and durability, and you will have the clothes and money to buy pictures.” – Gertrude Stein

She (Gertrude Stein) had such a personality that when she wished to win anyone over to her side she could not be resisted, and critics who met her and saw her pictures took writing of hers that they could not understand on trust because of their enthusiasm for her as a person, and their confidence in her judgement. She had also discovered many things about rhythms and the uses of words in repetition that were valid and valuable and she talked well about them.

I would have to work hard tomorrow. Work could cure almost anything, I believed then, and I believe it now.

I knew how severe I had been and how bad things had been. The one who is doing his work and getting satisfaction from it is not the one the poverty is hard on. I thought of bathtubs and showers and toilets that flushed as things that inferior people to us had or that you enjoyed when you made trips, which we often made….She had cried for the horse, I remembered; but not for the money. I had been stupid when she needed a grey lamb jacket and had loved it once she had bought it. I had been stupid about other things too. It was all part of the fight against poverty that you never win except by not spending. Especially if you buy pictures instead of clothes. But then we did not think ever of ourselves as poor. We did not accept it. We thought we were superior people and other people that we looked down on and rightly mistrusted were rich. It had never seemed strange to me later on to wear sweatshirts for underwear to keep warm. It only seemed odd to the rich. We ate well and cheaply and drank well and cheaply and slept well and warm together and loved each other.

Standing there I wondered how much of what we had felt on the bridge was just hunger. I asked my wife and she said, “I don’t know, Tatie. There are so many sorts of hunger. In the spring there are more. But that’s gone now. Memory is hunger.”

Then you could always go into the Luxembourg museum and all the paintings were heightened and clearer and more beautiful if you were belly-empty, hollow-hungry. I learned to understand Cezanne much better and to see truly how he made landscapes when I was hungry. I used to wonder if he were hungry too when he painted; but I thought it was possibly only that he had forgotten to eat. It was one of those unsound but illuminating thoughts you have when you have been sleepless or hungry. Later I thought Cezanne was probably hungry in a different way.

They say the seeds of what we will do are in all of us, but it always seemed to me that in those who make jokes in life the seeds are covered with better soil and with a higher grade of manure.

If, in your time, you have ever heard four honest people disagree about what happened at a certain place at a certain time, or you have ever torn up and returned orders that you requested when a situation had reached such a point that it seemed necessary to have something in writing, or testified before an inspector general when allegations had been made, presenting new statements by others that replaced your written orders and your verbal orders, you remembering, certain things and how they were to you and who had fought and where, you prefer to write about any time as fiction.

There is never any ending to Paris and the memory of each person who has lived in it differs from that of any other. We always returned to it no matter who we were nor how it was changed nor with what difficulties nor what ease it could be reached. It was always worth it and we received a return for whatever we brought to it.