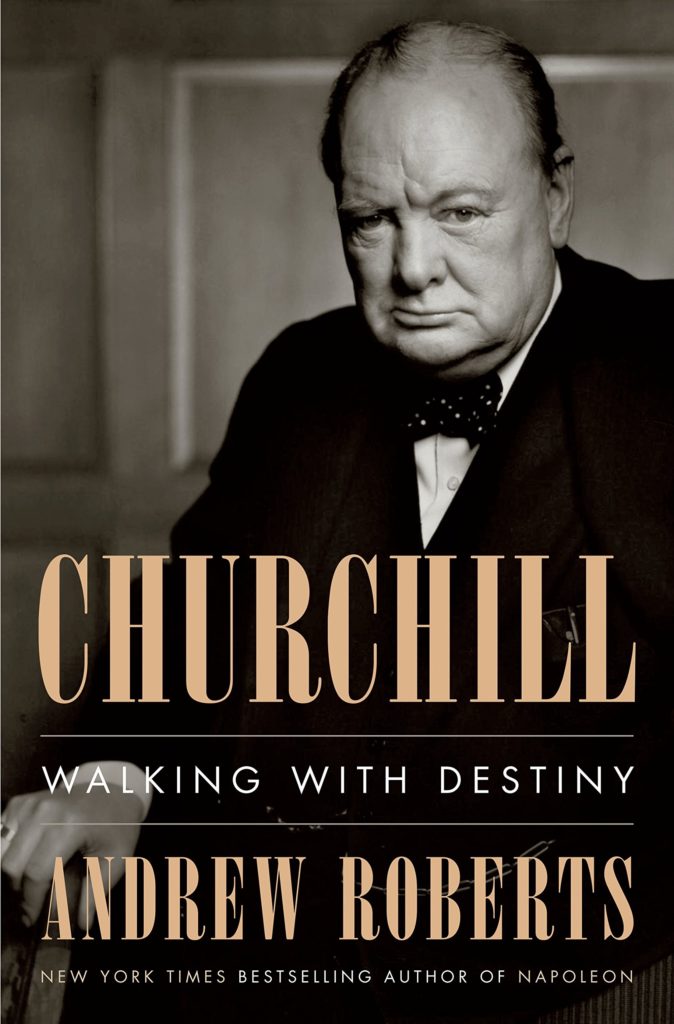

Churchill – Walking with Destiny by Andrew Roberts is for people who have an exceeding amount of enthusiasm about Winston Churchill. Its 982 pages (excluding extra notes) are certainly not for the faint hearted. Some time during last winter, this book was gifted to me by a very generous soul who truly understands and tolerates my obsession with history and Churchill. It landed in my hands, feeling like a weapon for self-defense. Reading history and of its great men is partially learning and practicing strategies for defending our civilisation during tumultuous times. This is the most outstanding part of the self-education that made Churchill who he was.

Andrew Roberts gave a talk about this book at Stanford a few months ago. He spoke of accumulating decades long of work for this book. Writing other books was great preparation for writing this one that he longed to do. New materials surfaced in recent years enabled him to include fresh personal and public records of that era. It was a great fifty minutes talk including Q&A. I was fascinated by his talk but left utterly unsatisfied. Up to this day, I think that event should have been at least a couple of hours long. Please please tell me more. I have so many questions to ask. Such is life. I would have to comfort myself through reading the book again.

I enjoyed reading and even more so listening to this book. But two flaws came up multiple times. There are some jumps in the text, sometimes within a paragraph, leaving me puzzled why the author thought it was a good idea to insert a quote or his analysis there. There is occasional repetition across chapters, although not too severely. For a book of this length, it might have been intentional to remind the reader of the text from previous chapters. Entirely forgivable, I suppose.

The texts wrapped in single quotes below are from Churchill himself. The part without quotes are from the author. The sources of the other texts are given as in the book.

‘I was conscious of a profound sense of relief,’ he later wrote. ‘At last I had the authority to give direction over the whole scene. I felt as if I were walking with destiny, and that all my past life had been but a preparation for this hour and for this trial . . . I thought I knew a good deal about it all, and I was sure I should not fail. Therefore, although impatient for the morning, I slept soundly and had no need for cheering dreams. Facts are better than dreams.’ He expressed the determination and anxiety of that momentous day when he spoke to Lord Moran in 1947, rather more colloquially than he did in his memoirs: ‘I could discipline the bloody business at last. I had no feeling of personal inadequacy, or anything of that sort. I went to bed at three o’clock, and in the morning I said to Clemmie, “There is only one man who can turn me out and that is Hitler.”’

‘I displayed the smiling countenance and confident air which are thought suitable when things are very bad.’

‘If we open a quarrel between the past and the present, we shall find that we have lost the future.’

The Atlantic Charter was announced on 14 August, which was the first moment the world knew that Roosevelt and Churchill had met, and that they were in total accord about the underlying principles for the world they wanted to build after the extirpation of Nazism. It provided a potent rallying cry for the forces of freedom, so that people could feel they had something inspiring to fight for, and not just something evil to fight against.

‘Winston had never been fond of Dill,’ Alan Brooke wrote after the war. ‘They were entirely different types of characters, and types that could never have worked harmoniously together. Dill was the essence of straight forwardness, blessed with the highest of principles and an unassailable integrity of character. I do not believe that any of these characteristics appealed to Winston, on the contrary, I think he disliked them as they accentuated his own shortcomings in this respect.’

‘This is the lesson: never give in. Never give in. Never, never, never, never – in nothing, great or small, large or petty. Never give in except to convictions of honour and good sense. Never yield to force; never yield to the apparently overwhelming might of the enemy.’ He (Churchill) then announced that he would like to alter a word in the verse dedicated to him: ‘I have obtained the Head Master’s permission to alter “darker” to “sterner” . . . Do not let us speak of darker days; let us speak rather of sterner days. These are not dark days: these are great days – the greatest days our country has ever lived – and we must all thank God that we have been allowed, each of us according to our stations, to play a part in making these days memorable in the history of our race.’

‘The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward…The wider the span, the longer the continuity, the greater is the sense of duty in individual men and women, each contributing their brief life’s work to the preservation and progress of the land in which they live.’

‘Winston’s almost blind loyalty to his friends is one of his most endearing qualities.’

‘The temptation to tell a chief in a great position the things he most likes to hear is one of the commonest explanations of mistaken policy. Thus the outlook of the leader on whose decisions fateful events depend is usually far more sanguine than the brutal facts admit.’

‘Whether it be the ties of blood on my mother’s side, or the friendships I have developed here over many years of active life, or the commanding sentiment of comradeship in the common cause of great peoples who speak the same language . . . I cannot feel myself a stranger here in the centre and at the summit of the United States . . . This is a strange Christmas Eve. Almost the whole world is locked in deadly struggle, and, with the most terrible weapons which science can devise, the nations advance upon each other . . . Let the children have their night of fun and laughter. Let the gifts of Father Christmas delight their play. Let us grown-ups share to the full in their unstinted pleasures before we turn again to the stern task and the formidable years that lie before us, resolved that, by our sacrifice and daring, these same children shall not be robbed of their inheritance or denied their right to live in a free and decent world. And so, in God’s mercy, a happy Christmas to you all.’

When things are going well, he is good; when things are going badly, he is superb; but when things are going half-well, he is hell on earth. – Ismay on Churchill, 1942

‘The problems of victory are more agreeable than those of defeat, but they are no less difficult.’

‘Soldiers must die, but by their death they nourish the nation which gave them birth.’

‘The price of greatness is responsibility. If the people of the United States had continued in a mediocre station, struggling with the wilderness, absorbed in their own affairs, and a factor of no consequence in the movement of the world, they might have remained forgotten and undisturbed beyond their protecting oceans: but one cannot rise to be in many ways the leading community in the civilized world without being involved in its problems, without being convulsed by its agonies and inspired by its causes.’

‘‘It is in this that one finds his mastery of the House. It is the combination of great flights of oratory with sudden swoops into the intimate and conversational. Of all his devices it is the one that never fails.’ – Nicolson

‘We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.’

‘What is this miracle, for it is nothing less, that called men from the uttermost ends of the earth, some riding twenty days before they could reach their recruiting centres, some armies having to sail fourteen thousand miles across the seas before they reached the battlefield? What is this force, this miracle which makes Governments, as proud and sovereign as any that have ever existed, immediately cast aside all their fears, and immediately set themselves to aid a good cause and beat the common foe? You must look very deep into the heart of man, and then you will not find the answer unless you look with the eye of the spirit. Then it is that you learn that human beings are not dominated by material things, but by ideas for which they are willing to give their lives or their life’s work.’

‘That was the element,’ he added, ‘this possible change in the weather, which certainly hung like a vulture poised in the sky over the thoughts of the most sanguine.’

‘Where words are useless, silence is best.’

It was an integral part of Churchill’s leadership code never to scapegoat subordinates.

‘If you want your horse to pull your wagon, you have to give him some hay.’

‘We have our mistakes, our weaknesses and failings, but in the fight which this Island race has made, had it not been the toughest of the tough, if the spirit of freedom which burns in the British breast had not been a pure, dazzling, inextinguishable flame, we might not yet have been near the end of this war.’

‘Some people say that our extraordinary self-suppression, bashfulness, and reticence is the reason why we do not always figure in the forefront of triumphant declarations, but we nearly always get things settled the way we want.’

‘It is difficult to describe or imagine the loneliness of someone in Winston Churchill’s position with the burden of responsibility that he carried and the knowledge that however much he shared or delegated it, the ultimate decisions were his.’ – John Peck

Churchill was impressed on meeting Truman, describing him as ‘A man of immense determination. He takes no notice of delicate ground, he just plants his foot down firmly upon it.’

‘Fathers always expect their sons to have their virtues without their faults.’

One of the few criticisms Churchill ever made of the 1st Duke of Marlborough was that he never wrote his memoirs: ‘He seems to have felt sure that the facts would tell their tale.’115 Churchill’s own monument was not going to be made ‘by piling great stones on one another’, as he put it, but by these war memoirs.

‘In War: Fury. In Defeat: Defiance. In Victory: Magnanimity. In Peace: Goodwill.’

I have known finer and greater characters, wiser philosophers, more understanding personalities, but no greater man. – Dwight D. Eisenhower on Churchill

Churchill was right when he wrote that all his past life had been but a preparation for the hour and trial of his wartime premiership. His early mastery of the ‘noble’ English sentence, and his wide reading as a subaltern, enabled him to produce his magnificent wartime oratory. His time in Cuba taught him coolness under fire, and how to elongate his working day through siestas. His experience in the Boer War exposed him to the deficiencies of generals. His time as a pilot and as secretary of state for air made him a champion of the RAF long before the Battle of Britain. His writing of Marlborough prepared him for synchronised decision-making between allies. His penchant for always personally visiting the scenes of action, such as the Sidney Street Siege and Antwerp, prepared him for the morale-boosting visits around Britain during the Blitz. His fascination for science, fuelled by his friendship with Lindemann, led him to grasp the military application of nuclear fission. His writing about Islamic fundamentalism prepared him for the fanaticism of the Nazis. His prescient, accurate analysis of Bolshevism laid the ground for his Iron Curtain speech, and his introduction of National Insurance and old age pensions with Lloyd George before the First World War prepared him for accommodating the welfare state after the Second. Above all his experiences in the Great War – preparing the Navy, the Dardanelles debacle, his time in the trenches and as minister of munitions – all gave him vital insights that he put to use in the Second World War.

‘Men and kings must be judged in the testing moments of their lives. Courage is rightly esteemed the first of human qualities because . . . it is the quality which guarantees all others.’

‘The reasonable man adapts himself to the world,’ George Bernard Shaw wrote in ‘The Revolutionist’s Handbook’; ‘the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.’

‘Man is spirit,’ Churchill told the ministers of his Government just before his resignation in April 1955. What he meant was that, given spirit – by which he meant the dash, intelligence, hard work, persistence, immense physical and moral courage and above all iron willpower that he himself had exhibited in his lifetime – it is possible to succeed despite material restraints. He himself succeeded despite parental neglect, the disapproval of contemporaries, a prison incarceration, a dozen close brushes with death, political obloquy, financial insecurity, military disaster, press and public ridicule, backstabbing colleagues, continual misrepresentation and even, from some quarters, decades of hatred, among countless other setbacks. With enough spirit, he believed that we can rise above anything, and create something truly magnificent of our lives. His hero John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, won great battles and built Blenheim Palace. His other hero, Napoleon, won even more battles and built an empire. Winston Churchill did better than either of them: the battles he won saved Liberty.