In this book, Andrew Grove talked to us about strategic inflection points: what they are, how to identify them, how to separate the signals from the noise, how to lead your business through the tough transitions and emerge from them stronger. Finally he offered advice on dealing with a career inflection point. In his own words:

In this book, Andrew Grove talked to us about strategic inflection points: what they are, how to identify them, how to separate the signals from the noise, how to lead your business through the tough transitions and emerge from them stronger. Finally he offered advice on dealing with a career inflection point. In his own words:

this book is about the impact of changing rules. It’s about finding your way through uncharted territories. Through examples and reflections on my and others’ experiences, I hope to raise your awareness of what it’s like to go through cataclysmic changes and to provide a framework in which to deal with them

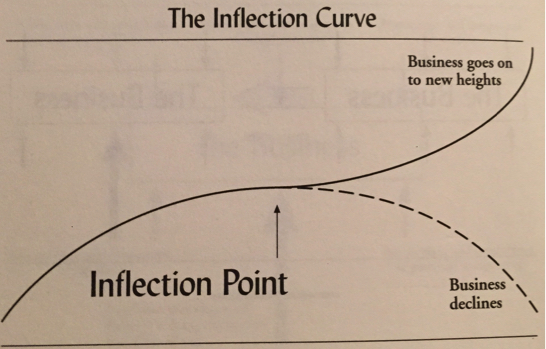

Given a curve, an inflection point is where the rate of change of the slope of the curve changes sign. In this book it is the time and place where the second derivative of the curve changes its sign from negative to positive. The figure below cited from the book illustrates this change. However, in reality, it is very challenging to pinpoint when exactly this inflection point takes place, what causes it and how to handle it. In this book, Andrew Grove shared his insights though both his own experience of navigating Intel through multiple challenges and observations of the other players in the computer industry.

Andrew Grove used the change of direction of the company Next as an example to illustrate a strategic inflection point in the computer industry. After leaving Apple in 1985, Steve Jobs started a new company, Next, to create the “Next” generation of superbly engineered hardware, a graphical user interface that was even better than Apple’s Macintosh interface and an operating system that was capable of more advanced tasks than the Mac. Unfortunately he and the team were oblivious to the new development that Microsoft had made in the PC domain, Windows. I like Andy’s way of capturing this: It was as if Steve Jobs and his company had gone into a time capsule when they started Next. They worked hard for years, competing against what they thought was the competition, but by the time they emerged, the competition turned out to be something completely different and much more powerful. This threw Next into a strategic inflection point. Eventually, Jobs pivoted Next to become a software company instead of a vertical hardware company.

Andrew discussed about the six forces affecting a business. The six forces are:

- power, vigor and competence of existing competitors, complementors, customers, suppliers and potential competitors

- the possibility that what your business is doing can be done in a different way.

He detailed the potential impact of a 10X force that could arrive from any one of the six forces or their combinations. For example, focusing on changes from customers: customers drifting away from their former buying habits may provide the most subtle and insidious cause of a strategic inflection point….Businesses fail either because they leave their customers, i.e., they arbitrarily change a strategy that worked for them in the past (the obvious change), or because their customers leave them (the subtle one).

He gave many examples of inflection points to help us identify the 10X forces in industries other than high-tech. For example, the impact of Walmart moving into a small town on small grocery stores, that of sound movies take over the silent movies, and how containerization transformed the shipping industry.

One very detailed discussion in the book is about the transition of the computer industry from a vertical one to a very different horizontal one. This potentially could be extended and applied to other industries too.

Horizontal industries live and die by mass production and mass marketing. They have their own rules. The companies that have done well in the brutally competitive horizontal computer industry have learned these implicit rules. By following them, a company has the opportunity to compete and prosper. By defying them, no matter how good its products are, no matter how well they execute their plans, a company is slogging uphill.

In this book, Grove prescribed three rules for succeeding in a horizontal industry.

- Do not differentiate without a difference. Do not introduce improvements whose only purpose is to give you an advantage over your competitor without giving your customer a substantial advantage.

- In this hypercompetitive horizontal world, opportunity knocks when a technology break or other fundamental change comes your way. Grab it. The first mover and only the first mover, the company that acts while the others dither, has a true opportunity to gain time over its competitors – and time advantage, in this business, is the surest way to gain market share.

- Price for what the market will bear, price for volume, then work like the devil on your costs so that you can make money at that price. This will lead you to achieve economies of scale in which the large investments that are necessary can be effective and productive and will make sense because, by being a large-volume suppliers, you can spread and recoup those costs. By contrast, cost-based pricing will often lead you into a niche position, which in a mass-production-based industry is not very lucrative.

I was particularly drawn to one story told in this book: In the midst of the memory crisis, Andrew Grove asked Gordon Moore, “If we got kicked out and the board brought in a new CEO, what do you think he would do?” Gordon answered without hesitation, “He would get us out of memories.” Andrew stared at him, numb and then said, “Why shouldn’t you and I walk out the door, come back and do it ourselves?”

The Route to Survival (advice from the book, roughly in the order of identifying inflection points, differentiating signal from noise, handling the chaos, how to rein in chaos):

The more complex the issues are, the more levels of management should be involved because people from different levels bring completely different points of view and expertise to the table, as well as different genetic makeups. The debate should involve people outside the company, customers and partners who not only have different areas of expertise but also have different interests.

When dealing with emerging trends, you may very well have to go against rational extrapolation of data and rely instead on anecdotal observations and your instincts.

I cannot stress this issue strongly enough. It takes many years of consistent conduct to eliminate fear of punishment as an inhibitor of strategic discussion. It takes only one incident to introduce it. News of this incident will spread through the organisation like wildfire and shut everyone up.

The old order will not give way to the new without a phrase of experimentation and chaos in between. The dilemma is that you cannot suddenly start experimenting when you realise you are in trouble unless you have been experimenting all along. It is too late to do it once things have changed in your core business. Ideally, you should have experimented with new products, technologies, channels, promotions and new customers all along.

How do we know whether a change signals a strategic inflection point? The only way is through the process of clarification that comes from broad and intensive debates.

Resolution comes through experimentation. Only stepping out of the old ruts will bring new insights.

Develop a new industry mental map. This map is composed of an unstated set of rules and relationships, ways and means of doing business, what’s “done” and how it is done and what’s “not done”, who matters and who doesn’t, whose opinion you can count on and whose opinion is usually wrong, and so on….knowing these things has become second nature.

Clarity of direction, which includes describing what we are going after as well as describing what we will not be going after, is exceedingly important at the late stage of a strategic transformation.

To make it through the valley of death succesfully, your first task is to form a mental image of what the company should look like when you get to the other side. This image not only needs to be clear enough for you to visualize but it also has to be crisp enough so you can communicate it simply to your tired, demoralized and confused staff.

Seeing, imagining and sensing the new shape of things is the first step. Be clear in this but be realistic also. Do not compromise and do not kid yourself. If you are describing a purpose that deep down you know you cannot achieve, you are dooming your chances of climbing out of the valley of death.

If you are in a leadership position, how you spend your time has enormous symbolic values. It will communicate what is important or what is not far more powerfully than all the speeches you can give.

Assigning or reassigning resources in order to pursue a strategic goal is an example of what I call strategic action. I’m convinced that corporate strategy is formulated by a series of such actions, far more so than through conventional top-down strategic planning.

Should you pursue a highly focused approached, betting everything on one strategic goal, or should you hedge?…I tend to believe Mark Twain hit it on the head when he said, “Put all of your eggs in one basket and WATCH THAT BASKET.”…It is very hard to lead an organisation out of the valley of death without a clear and simple strategic direction…While you are going through the valley of death, you may think you see the other side, but you cannot be sure whether it is truly the other side or just a mirage. Yet you have to commit yourself to a certain course and a certain pace, otherwise you will run out of water and energy before long. If you are wrong, you will die. But most companies do not die because they are wrong; most die because they do not commit themselves. The fritter away their momentum and their valuable resources while attempting to make a decision. The greatest danger is in standing still.

While struggling with a 10X force, you cannot change a company without changing its management .

Finally, Andrew Grove draw parallel of the career inflection points to the business strategic ones. Career inflection points caused by a change in the environment do not distinguish between the qualities of the people that they dislodge by their force.

The desire for a different lifestyle, or the fatigue that sets in after many years of doing a stressful job, can cause people to re-evaluate their needs and wants, and can build to a force as powerful as any that comes from the external environment. Put another way, your internal thinking and feeling machinery is as much as part of your environment as an employee as your external situation. Major changes in either can affect your work life.

The chapter on Career Inflection Points teach us a few lessons:

- Each person, whether he is an employee or self-employed, is like an individual business. Your career is literally your business, and you are its CEO….It is your responsibility to protect your career from harm and to position yourself to benefit from changes in the operating environment.

- initiate your career transition in your own time rather than having it initiated for you by outside circumstances.

- Be alert to changes. Go through a mental fire drill in anticipation of the time when you may have a real fire on your hands. Be a little paranoid about your career.

- Be aware of the sources that might keep you from recognizing the danger, for example, the inertia of previous success, the fear of giving that up and the fear of change. Denial will only cost you time and lead you to miss the optimal moment for action.

- While experimenting for change, avoid random motion. Look for something that allows you to use your knowledge or skills in a position that is more immune to the wave of changes you have spotted. Better yet, look for a job that takes advantage of the changes in the first place. Go with the flow rather than fight it.

- Andrew’s final advice of the book on career transition: looking back may be tempting, but it is terribly counterproductive. Donot bemoan the way things were. They will never be that way again. Pour your energy, every bit of it, into adapting to your new world, into learning the skills you need to prosper in it and into shaping it around you. Whereas the old land presented limited opportunity or none at all, the new land enables you to have a future whose rewards are worth all the risks.

This concludes my summary of the book. I came across this book from two sources: Ben Horowitz’s book that I wrote about in previous blog and the leadership courses that I have been attending at Stanford. To me, if there are multiple significant and credible sources that mention a book or a person or a topic, that qualifies it as a definite “signal” for me to look into. I am glad that I read this book as a result of that. Although it appears that a few concepts conveyed in the book are contradictory to those of other books. For example, here advocating for being a first mover, while as Adam Grant’s Originals and Peter Thiel’s Zero to One recommend to beware the disadvantages of that and that the conventional view might have over-estimated the benefit for first movers. In my opinion, the correct way to read leadership, management and entrepreneurship books is to get different perspectives and to broaden my thinking, to see how the insights were derived from the particular circumstances, and to learn what fundamental attributes of the authors enabled them to navigate through the difficult times and lead their business to success. It is useful having read these books to think about the values of what has been regarded as wrong or bad practices. The goal is absolutely not to memorize the rules, as there could never be a rigid set of prescribed one-size-fit-all advices for the constantly evolving world.